In this week’s feature of our Black History Month celebration, we go back in time to learn more about the life of Esteban Hotesse. Hotesse was the only Dominican-born member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen, the first all-black group of military pilots in the U.S. Armed Forces, and one of the few soldiers born in a Spanish-speaking nation to serve the United States during World War II.

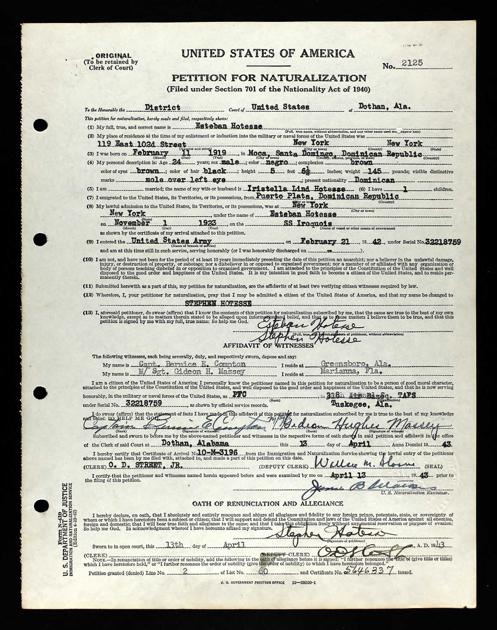

Hotesse was born on February of 1919 in Moca, Dominican Republic. At age four, he migrated to the United States with his mother and sister, traveling through Ellis Island and settling in Manhattan, like many Dominicans at the time. In 1942, Hotesse enlisted in the United States Army Air Corps and was assigned to the 619th Bombardier Squadron, where he earned the rank of second lieutenant. In 1943, after serving for one year, he and his Puerto Rican wife Iristella Lind applied for U.S. citizenship.

After public pressure by civil rights leaders to incorporate African American soldiers to more crucial positions in the Army Air Corps, Hotesse’s squadron was included in the newly-reformed 477th Bombardier Group M, which was relocated to Freeman Army Airfield in Kentucky in 1945. Here, the group would become famous for their role in the civil rights struggle that came to be known as the Freeman Field mutiny.

In April of 1945, word got out that the Colonel in charge of the base had created Jim Crow segregated officer clubs, which at the time were supposed to be integrated. In protest, Hotesse and other Tuskegee Airmen of his squadron entered the whites-only club peacefully, and were arrested for breaking the rules of the base. A total of 101 officers of the 477th Bombardier Group M, including Hotesse, were arrested and eventually released without serious consequence.

Hotesse passed away less than three months later when his plane crashed in the Ohio River. He was only twenty-six at the time, and left behind a wife and two young daughters, who today reside in New York City. For decades after his death, Hotesse’s role in the U.S. Armed Forces, and in the Freeman Field mutiny, was unknown. Hotesse’s story was discovered by Edward De Jesus, research associate at the Dominican Studies Institute at CUNY, New York. While poring over hundreds of military records, De Jesus came across Hotesse’s name in an Army Enlistment Record, and followed the paper trail to discover he had been a Tuskegee Airman, and the only Dominican of the squadron.

Hotesse’s and others’ dedication to integration and equality during the Freeman Field mutiny became an important milestone in ending segregation in the armed forces, as well as a model for peaceful civil disobedience later used by many activists during the Civil Rights Movement.