In the United States, 20 people die every day waiting for an organ transplant. Meanwhile, every 10 minutes someone is added to the national transplant waiting list. These figures give us an idea of the magnitude of the problem: in August 2017, 116,000 people were waiting for an organ. While the rate of organ donors grows moderately, that of patients whose lives depend on a transplant goes faster. Every year, the organ deficit grows, despite the fact that around 50% of adults in North America are registered as donors.

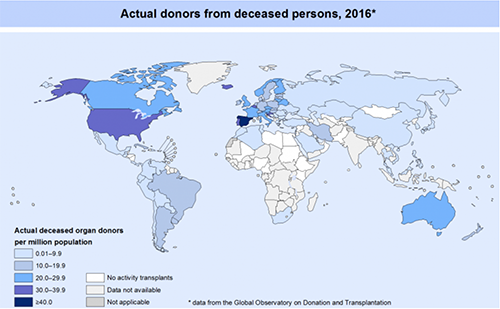

In 2017*, there were 31.7 deceased donors per million inhabitant (pmp) in the U.S., only surpassed by Spain, a world leader that reaches the figure of 47.1. These donors made possible 109.7 and 113.4 transplants pmp in these two countries, respectively. This Spanish average is much higher than that the Europe continent, 61.4.

When comparing the rates in Latin America, the averages fall radically. At the top of the deceased donors pmp 2017 raking we have Uruguay (18.9), Brazil (16.3), Argentina (13.4), and Cuba (12.4). Followed by Chile (9.6), Colombia (8.9), Costa Rica (4.5), and Panama (4.2). At the lower end there’s Peru (1.6), and Guatemala (0.1). In our continent, the number of organ transplants— which reveals the state of the healthcare system—is very low. In Latin America, on average 29.4 organs were transplanted pmp; 59 when we include Canada and the U.S. In addition to low number of transplants, few people are organ donors, with respect to trends in other countries.

Reviewing the global figures of transplants allows some optimism: between 2010 and 2017 the number duplicated. In 2016, over 120,000 transplants were performed in the world. But this growth hardly has the contribution of Latin America, whose rate is less than 1%. However, this increase is still deficient with respect to the needs. Right now, around 250,000 people in the world are waiting for an organ to save their lives.

Every person has a great potential for donation: a heart, two lungs, two kidneys, a pancreas, a liver, the intestines, in addition to the bone marrow, bones, eye tissues, cardiac valves, vascular segments, ligaments, etc. Unfortunately, since each organ is a very valuable asset, an illegal and terrible industry has engendered: organ trafficking. This commercial activity has its variants: there are people in poverty who decide to sell some part of their bodies; or mafias who, using the most extreme forms of violence, kidnap people, transfer them from one country to another, and deliver them to be subjected to surgical interventions with the purpose of extracting organs without consent. It has come to the point, as the reader can imagine, that some of these abducted people have lost their lives in these clandestine operating rooms that, most of the time, do not meet the minimum sanitary conditions for interventions of such complexity. Although it seems surprising, even today, in the XXI century, in Africa, Asia and Latin America these events continue to occur, in the most extreme contempt for the lives of others.

Spain’s model is, without a doubt, a successful case that deserves to be studied. There are multiple factors that make its extraordinary performance possible. For one, many people donate their organs, as a result of information and awareness campaigns. Additionally, medical specialists in intensive care are properly trained to detect potential donors, address the family and talk about it. Around 85% of the approaches have a positive response. Lastly, the essential element of this Spanish success is their hospital network, technically and professionally prepared, always ready to act when an organ becomes available for transplant.

In our Latin America, campaigns that promote organ donation are infrequent and spasmodic. Despite being an essential subject for the life of many people, it is hardly mentioned in school. There is a clear disproportion between the number of patients waiting to be saved and the culture of donating, which is almost nonexistent.

A culture of organ donation is inseparable from a health system trained in performing transplants. The possibility of implementing it depends on many factors: it must be a State policy; it must have the necessary budget for long cycles: it compels the participation of universities, hospital centers, medical specialists, patient associations, schools, the media and more. In brief, it needs agreements and consensus. It requires a societal commitment to the project and a State to make it possible.

*Source: Data retrieved from Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation

Para español lea: La donación de órganos

Nos leemos en Twitter por @lecumberry