Frequently, we forget that Belize is one of the sovereign nations of Central America. In my opinion, there are multiple reasons to explain this phenomenon. The first one I will mention now is that, until 1973, it was named British Honduras; it was a United Kingdom colony. In negotiations for its independence, the first step was to change its name to Belize (or Belice in Spanish). In fact, when the infamous Hurricane Hattie literally destroyed Belize City, on the dreadful October 31st, 1961, Latin American newspapers referred to the event as the “tragedy in British Honduras”. Belize City, also known as Puerto Valiz, was devastated. Forced by the situation, the authorities moved the capital to Belmopan, which was built in 1960. It has remained the capital since the move, despite being the third most populous city in Belize.

Central America’s British Colony

Belize achieved its full independence in 1981. Its territory expands almost 23 thousand squared kilometers (8.90 thousand squared miles), with a population of about 290 thousand people. Although Spanish and Belizean Creole predominate—it is estimated that almost 80 thousand people are native speakers of this language—in quotidian use of languages, the country’s official language is English.

Because it is a small territory, which has a total population comparable to that of any small city in the rest of the region, and is still under the influence of England, there is a perception that Belize is a foreign nation, or separate, to the orchestra of Latin America. In fact, even after signing its independence in 1981, it was ratified that the government in Belize would remain a parliamentary democracy, based on the Westminster System (which was a type of regime adopted in many parts of the world by former British colonies, as a phase towards complete independence). At least nominally, Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom is the sovereign of the country. Its affiliation to England was surprising and bluntly felt during the intense debates that occurred in 1982 around the Falklands War. When the historic United Nations (UN) vote took place, Latin American representatives, as a single bloc, backed Argentina’s position; instead, Belize cast its vote in the opposite direction: the Malvinas archipelago should be recognized as territory under English sovereignty.

Belize is the small Central American territory located east of Guatemala and south of Mexico. Its entire coast faces the Caribbean Sea. Its economy, very small for obvious reasons, is primarily has an agricultural and agroindustry foundation. Its main exports are sugar canes, plantains, and citric fruits. In the last three decades, tourism has been rapidly increasing to the point of becoming a significant weight in the local economy, equal to 40% of the GDP. Moreover, tourism generates between 45 and 48 thousand jobs, which is equivalent to a third of the active population. Other industries such as trade, minerals, seafood exportations, and a modest oil production, are also relevant economic activities in Belize.

Poverty, Violence, and Illegal Activities

Similar to other countries in the area, Belize is a country with high poverty indexes. Available statistics are not completely reliable, because of mistakes at different levels. According to different documents, generally, elaborated by foreign entities, between 35 and 50% of the population lives below the poverty line (i.e. families that do not have a minimum income access food and basic services, and that live with less than $1.9 a day). In 2017 a report, UNICEF pointed out that around 20% of children suffer from malnutrition, at some level. The organization Salud por Derecho conducted a study on the capacity of Latin American and Caribbean countries to respond to HIV. The results drew attention to the case of Belize, which only has 36% of the resources necessary for these purposes.

Amidst this field of difficulties, violence indicators in Belize are among the worst in the world. In recent years, Belize has been at the forefront of the homicide rate per 100 thousand inhabitants, along with Honduras, Venezuela, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Journalists who have visited the country in recent years have narrated that it is common to hear the inhabitants of the country recite the phrase, “you can die at any time,” with resignation. There is a history of murders in Belize, sometimes without an explanation; authorities look helpless when faced with this reality. According to the UN, in 2012 there were 146 murders committed in the small country, which speaks to the seriousness of the situation. This is equivalent to a rate of 44 deaths per 100 thousand inhabitants.

However, a reason for this is a more profound and dangerous problem: the use of Belize as a safe heaven, refuge, or transit stop for drug trafficking, gangs from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, and Mexican drug cartels. Some of Belize’s islands—which are invaluable to humanity, because of its coral reefs—are used for drug, weapon, wood, exotic species, and even human trafficking operations. Security experts have warned that Belize’s geographical location is strategic to obtain drugs produced in South America, especially cocaine, which will continue its way to Mexico and the United States. Moreover, there are allegations that warn that internationally wanted terrorists have taken refuge in Belize.

Similarly to what occurs in neighboring countries—Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador in Central America’s Northern Triangle, where gangs dedicated to drug trafficking and other illicit activities have successfully penetrated the judicial system and police forces—, impunity and corruption have led to violence proliferation, which specially affects the youth. Fights between gangs are a kind of infernal circle, whose irradiation affects the whole society. In Belize City alone, whose population does not reach 60 thousand inhabitants, 14 gangs face off. Despite some recent efforts, the solutions seem small in relation to the magnitude of the problems.

Environmental Challenges

Belize faces further threats, which are worth bringing attention to. One of them its geographical vulnerability to climate change that, with each year, increases the risk of producing food, which is vital for the economy and feeds about 40 thousand families. Cycles of droughts and floods have been deteriorating production indicators. According to experts, Belize has lost an average of 3 to 4% of its GDP annually as a result of the weather, for the past five years. Farmers are defenseless, among other reasons, because their modest incomes do not allow them to purchase insurance policies to provide relief in times of difficulty. On top of this, many of the homes and Belize fields’ infrastructure could hardly resist, for example, a category 3 hurricane. If faced with a category 4 or 5 hurricane, destruction would unavoidable.

Another environmental hazard threatens Belize’s barrier reef—the most important in the Americas and the second largest on Earth, which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996. Over 500 different types of fish and almost 1500 marine fauna species are part of this heritage, besieged by overfishing, predatory tourism, and the excesses committed by oil exploration. In 2009, it entered the list of heritage sites in danger.

Faced with a group that favored the economic urgencies of this poor country, environmental groups promoted a referendum in 2012, which had an unequivocal result: 96% of the participants said ‘No’ to the oil activities in the area. In December of 2017, the government headed by Dean O. Barrow banned oil exploration. Six months later, in June 2018, UNESCO withdrew the classification of heritage in danger, with which the coral reef fully recovered its patrimonial status.

Territorial Dispute

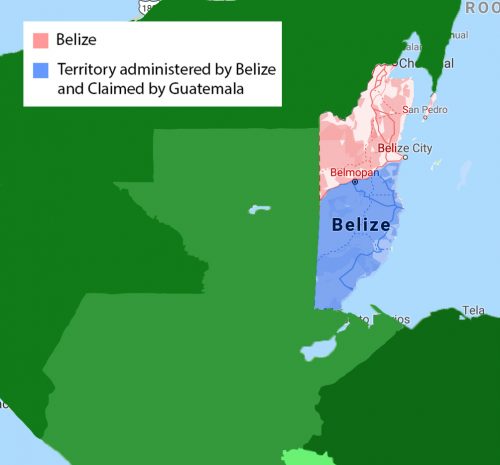

On April 10, another event will take place in Belize that can be considered a milestone in the territorial disputes of the continent. Guatemalan claims over a part of Belize’s territory—a little more than 11 square kilometers—go back to 1859. That represents almost half of the country’s territory. In April 2018, there was a referendum organized in Guatemala in which 96% of the voters— barely a quarter of the electorate chose to submit the territorial dispute to the International Court of Justice. Next month it is Belize’s turn to ask its constituents whether or not they agree to submit to the opinion of the aforementioned International Court of Justice.

Needless to say, this is an undeniably complex dilemma. On one hand, the triumph of the ‘No’ would extend a controversy of a century and a half, without there being, until now, another mechanism in sight to solve the dispute. On the other hand, voting ‘Yes’ risks losing almost half of the territory—an extraordinary risk if you think about the size of the country and the poverty in which a part of its population lives.

The enemies of the referendum maintain that Belize, unlike Guatemala, does not have the financial capacity to hire international lawyers to act in defense of its arguments. If the International Court of Justice ruled in favor of Guatemala, a crisis of unprecedented proportions would occur; a legal and institutional hurricane that would have demographic, political, economic, and cultural implications. There is no precedent of an event in which, under the dictates of a court, a nation that lost a substantive part of its territory welcomed the decision peacefully.