In addition to meeting with a group of Caribbean heads of States and welcoming Fabiana Rosales—the first lady of the Venezuelan interim government of Juan Guaidó—, escalating his confrontation policy with Maduro’s regime to promote a change in Venezuela, these last couple of weeks Trump advanced without further thought on two fronts: First, he harshly criticized his closest ally in the region—particularly in relation to the Venezuelan crisis—the President of Colombia, Iván Duque, and falsely accused him of not doing anything to combat drug trafficking. Trump fails to understand that, in addition to the impact of the Venezuelan migration, drug trafficking is one of the principal motivations for Duque’s fight against the Maduro regime. The regime’s institutions and Armed Forces are involved with drug trafficking and money laundering, to the point that the presence of the ELN in Venezuela has acquired an alarming dimension.

Second, Trump announced cutting financial and cooperation assistance towards the countries of the Central American Northern Triangle, which are affected by the violence rooted in drug trafficking. In addition to the violence, there is a grave economic crisis of humanitarian magnitudes in the region. These concurrent realities cause important flows of migrants who march through Mexico towards the southern border of the United States, where Trump focuses on one of the central pieces of his populist and xenophobic rhetoric when talking about the problems of the US and promoting an emergency, which he proposes to solve by building a wall.

Trump does not seem to comprehend that the migration originated in the Central American Northern Triangle, composed of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, can be reduced to one word: the citizens do not migrate. They escape.

Anyone who followed the news of the last quarter of 2018, for example, will remember it with sadness: stories of mothers and fathers that, while carrying babies in their arms, walked two, three, and even four thousand kilometers to flee from the terrible living conditions in which they live. Along the path, the migrants barely eat; they sleep on the floor; and are exposed to the weather conditions. They also take risks only because they are desperate: they cross borders illegally, traverse large rivers without any protection, and, even worse, are robbed, kidnapped, and killed. In the case of children that travel without their parents—imagine for a moment the experience that must be for a child 8, 9, or 10 years old to embark on a journey with adult strangers—, they are raped or disappear devastatingly frequently. According to a UNICEF Mexico statement, in 2015 alone, there were 35 thousand unaccompanied minors who left the countries of the Northern Triangle towards Mexico or the US. Between 2013 and 2017, the US authorities reported detaining 180 thousand minors—again, 180 thousand minors—who traveled unaccompanied.

The Atlas of migration in Northern Central America, published by ECLAC and FAO in December 2018, asserts that between 2000 and 2010, the number of Latin Americans who lived outside of their native country increased by 32%. In the case of Central America, this figure was 35%. When zooming in on the three countries that make up the Northern Triangle of Central America, it is 59%—94% when only considering Honduras.

There is a series of different and complex phenomenon under the migration category. Organized caravans are only one of them. There are also organizations, made up of “coyotes”, which profit from crossing illegal migrants. The coyotes, in turn, pay the gangs, which are mostly drug traffickers, for allowing them to run their business. In addition to the aforementioned case of unaccompanied minors, there are those who undertake the path to achieve family reunification, families traveling in blocks, migrants in transit conditions (for example, those who cross Mexico on their way to United States), those who are detained and deported back to their countries, those who make the opposite way and return to their countries—many times facing dangers similar to those experienced on the outward journey—, those who are victims of legal and police violence, those who are subjected by the anti-immigration policies of the Trump administration, those who flee and are persecuted by criminals from their countries of origin, and many more cases that include shameful chapters of racism and xenophobia. Migration is, increasingly, a very complex set of typologies, which can hardly be met with general measures or, worse, with mere prohibitions.

Multiple studies on this phenomenon—a substantive tendency of the first stretch of the 21st century—agree on the causes that explain the decision to migrate. People feel ‘expelled’ from the place where they live and are forced to leave. There are diverse variables that intervene; to begin to understand this migration we must recognize that it is the product of an accumulation of factors. In general terms, two forces interact as triggers: violence and the lack of job opportunities. When their life is in danger, either by threats inside or outside the home—as happens with the proliferation of gangs in the three countries—, while it being impossible to finding a job or obtain a steady income, heads of families and young people embark on a journey full of uncertainty and danger.

But, at the same time, these two factors are inscribed in a larger set of things: States that lack the capacity to protect the life, physical integrity, and property of citizens; political, judicial, and other institutions, eaten away by corruption; educational systems, particularly the official ones, of low quality and undermined by the lack of infrastructure, technology, equipment, and security for students and teachers; precarious and insufficient health centers; lack of public services, economic opportunities, minimal roads, transport networks, and many other things, whose listing would be long and incomplete.

Midst the framework of generalized poverty and slim to none expectations that things will change, climate change consequences begin to intensify in the region. In the three countries, poverty predominates. The poverty indexes in Guatemala and Honduras are scandalizing, 68 and 74%, respectively. When it comes to rural poverty, the figures skyrocket to 77 and 82%, according to the aforementioned ECLAC / FAO report. In El Salvador, rural poverty reaches 49% of its inhabitants.

Natural disasters are another reason for these migrations. I’m not referring to the incontrollable earthquakes that, when they hit, caused such devastation that whole populations had to abandon their homes and their ways of life. Instead, the net results of climate change, such as hurricanes, floods, and droughts. Why are a high percentage of those who emigrate people who leave the fields to try a life in another place? Because the historical cycles of summer and winter have been surpassed by cycles of destructive waters and droughts that reduce productivity in an extreme way. An evident example is the data on the fall in corn production: in 2015, between 60 and 70% of the crops were lost. This means that, of the 10.5 million people living in the tropical forest region, 3.5, approximately, need humanitarian assistance, because they do not have enough to eat.

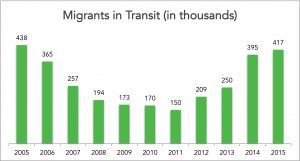

A brief review of the figures of migrants in transit (i.e. those who left from the three countries to the north, Mexico or the United States), between 2005 and 2015, allows us to visualize its massive nature. The graph below shows that, after a few years of decline, between 2005 and 2011, as of 2012 the trend rises as a result of the worsening of realities and expectations in the three countries. Between 2009 and 2017, the number of migrants from the northern triangle of Central America grew by 35%.

The peaks or highest migration moments closely correlate to the magnitude of the financial assistance and development cooperation programs of the US. Precisely, under the Obama administration, starting in 2008, a significant cooperation effort was put forth that resulted in a reduction of migratory numbers until 2012, according the numbers reported above. That year, financing decreased due to lack of agreement in the US Congress. Later, the Trump administration suspended that program, and eliminated it altogether last week. Therefore, we can anticipate that the worsening conditions in the region will increase migratory pressures.

In addition to migrating due to the mentioned factors in previous paragraphs, there’s an economic aspect worth mentioning. Despite the difficulties migrants face in the countries where they settle—in this case, predominantly Mexico and the US—they are able to send money or remittances to their relatives who stayed behind in the Northern Triangle. These remittances have a fundamental role in the economy of their respective countries. In 2016, Honduras received $3.8 billion; Guatemala, $7.4 billion; and El Salvador, $4.6 billion. These amounts represent no less than 20% of the GDP of Honduras, 17% of El Salvador, and 10% of Guatemala. The fundamental study of Canales y Rojas (2018) reports that 70% of the economically active population of the three countries in the United States has a job, even though most of them are low-skill.

Faced with these realities, the UN is promoting the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM). The agreement’s first draft was announced in July 2018, and presented in December for the member countries to subscribe to it. This document is based on three principles and twenty-three objectives. The principles that will govern the global agreement are common understanding, shared responsibility, and unity of purpose regarding migration.

The 23 objectives, which every citizen of the world should know, refer to the four phases of the process: Origin, Transit, Destination and Return. In essence, it involves mitigating and eradicating the causes that drive migration: they are an ambitious set of social, economic, institutional, environmental, and security challenges. From a broad perspective on the issue, addressing migration is a demand of our time; it involves developed countries as well as poor countries, from which the migrants leave. In the previous articles that I have devoted to the situation of the three countries, I insisted on highlighting the responsibility of the public powers and current governments. The Northern Triangle of Central America cannot continue suffering the vicissitudes of poverty; losing its young population and heads of family; and watching, helpless, as its children die or disappear in the hands of the criminals who lurk on the roads. This tragedy cannot be normalized.

The decision on the Central American case is not only turning a back on the regional and international consensus on the problem, worsening the migratory crisis, but also introduces a grave element of lack of confidence in Trump’s recent plans with the Caribbean heads of States. In the Caribbean, problems also demand transversal cooperation for development, including the risk of drug trafficking penetration and money laundering.

By attacking president Duque, ignoring his alliance and efforts, it is further perceived that Trump does not recognize the potential opportunity Latin America offers him, as well as the transversal, coherent and intersectional demands of foreign policy to solve hemispheric problems.

Chris Sabatini, a foreign policy professor at Columbia University, explores in a recent article analyzing this sea of contradictions: How can Trump make the regional alliance—needed to solve the crisis in Venezuela and develop opportunities present in the region—sustainable and lasting? To which we add: Are we sure that his real motivation is closer to a political calculation (for its electoral impact in Florida, a crucial state for his reelection), than the desire to design a foreign policy capable of facilitating change in Venezuela?

Para español lea Al Navío “Donald Trump mete la pata y la mete dos veces”