A professor from the Universidad de Oriente in Venezuela, also a biologist and oceanographer, emigrated to Pamplona, Navarra (in the north of Spain) in 2013, with his wife and three children. The couple set up a café downtown, in the Town Hall square. At the bar, serving coffee and arepas, he began to talk about the project he had been dreaming of since he was a teenager, with two friends: purifying groundwater and surface water (fresh and sea) with sunlight energy in order to obtain drinking water and to generate energy.

His name is Mikel Elguezabal and the project is called Egura Project, which translates from Basque as Sun and Water. In Euskera (the Basque language), eguzki is sun and ura is water.

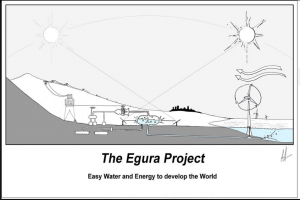

The technology that uses the sun’s energy has been known and used for centuries, Elguezabal comments to Iq Latino, but Egura Project’s focus is to expand and improve these ways of obtaining water for human consumption, irrigation and electrical energy on a global scale, in “the tropical and subtropical regions of the planet,” taking advantage of the long hours of sun exposure in these areas all year long.

Elguezabal plans to begin with an initial phase of cooperation in coastal villages, called Egura Cooperation Trials, between 2020 and 2023. Water can be pumped from the seas of these villages into an Egura pilot plant. It is a way of generating its own energy with “mechanical windmills, or electric pumps powered by solar panels and/or wind turbines,” Elguezabal explains to IQ Latino.

Once the seawater is extracted, it is taken to plankton filter tanks that would then feed other species in their laboratories of a future Aquaculture Unit of Egura Plants, which would operate simultaneously. The filtered water, continues Elguezabal, passes to thermosolar distillers that will separate the salts and send them to brine tanks. Part of that water goes to a main boiler of a thousand liters that is connected to a turbine. The energy to heat this boiler will be produced with metal reflectors that will surround its arch and large magnifying glasses that will cover it. The water is then sterilized.

The idea is that the project can also be used in inland regions to be applied to polluted aquifers, wells and rivers.

The dream is in the head of Elguezabal and his childhood friends César Augusto Dommar Valerio and Juan Carlos Rapffensperger López, since adolescence. It was 1995, and in front of the Gulf of Cariaco, in the state of Sucre (on Venezuela’s northeastern coast) they imagined “injecting” seawater into the subsoil “to obtain fresh water from re-condensate steam, and use that steam to move generating turbines” that his friends would build. But the salts were going to be lost, Elguezabal recalls, and salts are something they also want to take advantage of.

The dream began to materialize in 2013, in a library in Uharte, where they live, just outside the city, when he was doing a postgraduate degree in environmental agrobiology. The same year he and his famiy moved to that city. That’s where the name Egura was born.

Egura Project is still in its very initial phase: the search for the resources to make it real.

They will do a crowdfunding in Navarra, the Basque Country and Aquitaine (on the French side). They first want to produce a quality trailer for it, so they want to call an audiovisual competition to select the best filmmaker for the trailer. Elguezabal tells IQ Latino that they seek to convince 20 companies to finance this competition (they would need money for the prize, to pay the jury and the organizing committee and for the production of the trailer itself).

Once the trailer is made, this crowdfunding and other national crowdfundings will be launched in each country where the Egura Cooperation Trials (ECT’s) will begin to be implemented. They want to implement the ECT’S in coastal towns of Latin America (they would like to use the first crowdfunding to start in Venezuela, but that will depend on the situation there, or in Colombia), Africa, Asia, the Mediterranean, and Indian and Pacific oceans coasts. For this, they would hire an engineer and a biologist from each country where the Egura pilot plant operates, who would put the entire process into operation.

Elguezabal tells IQ Latino that he has received calls from the embassies in Madrid of Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Oman and Lebanon. He has also presented the project to several companies for their corporate social responsibility programs.

In phases posterior to the Egura Cooperation Trials, Egura Project would seek to replicate these plants at smaller scales: homes, villages with few inhabitants, hospitals, schools, libraries and food.

And, then, they would grant Egura’s patents, through an online platform, to small and medium enterprises of the countries where Egura Cooperation Trials have been made. These companies must work with a circular economy perspective, with recycling the material they use.

In addition to his two friends, his wife Yaile Acosta Núñez, a human rights lawyer, his mother Elizabeth Méndez Rodulfo, a marine biologist, accompanie Elguezabal on this project. Egura also counts on an ad honorem advisory council composed primarily of people from the Venezuelan diaspora.