On April 21, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control emitted a general license on Venezuela sanctions, heavily limiting the work of five U.S. oil-industry businesses that, until this date, were exempted from sanctions and had permission to operate in Venezuela. Chevron Corporation is the most notable among them. The other four are Halliburton, Schlumberger Ltd., Baker Hughes Co., and Weatherford International Plc.

Eric Farnsworth, Vice President of Council of the Americas, told IQLatino, “this new round of restrictions further tightens what the administration calls a campaign of maximum economic pressure, designed to starve the Maduro regime of resources and the ability to sustain its apparatus of popular control.”

Mr. Farnsworth added that the administration had been previewing this measure for some time and that it anticipated “these new steps will create a shock to the regime that will make it increasingly difficult to maintain itself in power.”

The Treasury Department had released the five companies from Executive Order 13850 (“Blocking Property of Additional Persons Contributing to the Situation in Venezuela”) since January 2019, authorizing them to operate in Venezuela in transactions involving Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PdVSA) in six different licenses. The most recent one was set to expire on April 22 and had to be reauthorized in some form or ended.

As reported in the New York Times, the decision to finally implement these restrictions occurred after a “fierce debate in the administration.” One side argued the U.S. should hold its corporate ground in Venezuela instead of opening more opportunities to Russia and China. The other insisted extending the provisions would help Maduro stay in power, and ultimately prevailed.

The Treasury Department’s expiring deadline coincided with the lowest price of crude oil futures ever—negative $38. Since then, it has increased to the $15 vicinity. In this context, Francisco Monaldi told Reuters, “The collapse in prices made it practically irrelevant if Chevron was there or not.” Adding that if the oil prices recover in three or four months, “it becomes more relevant.”

Chevron, which has operated in Venezuela since 1921, partners with PdVSA in four projects. Two of the projects—Petroboscán and Petropiar—alone, produced almost 25% of the country’s oil. However, according to Bloomberg News, production at Petropiar fell 58% from January to Mid-March of this year.

Now Chevron is barred from producing Venezuelan oil (including drilling, selling, and transporting), investing in its infrastructure (unless it is for safety reasons), and any financial transactions with PdVSA. The company’s spokesman, Ray Fohr, said that their “operations continue in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.” Adding that they continue to focus on their base business operations and supporting the 8,800+ people who work with them and their families.

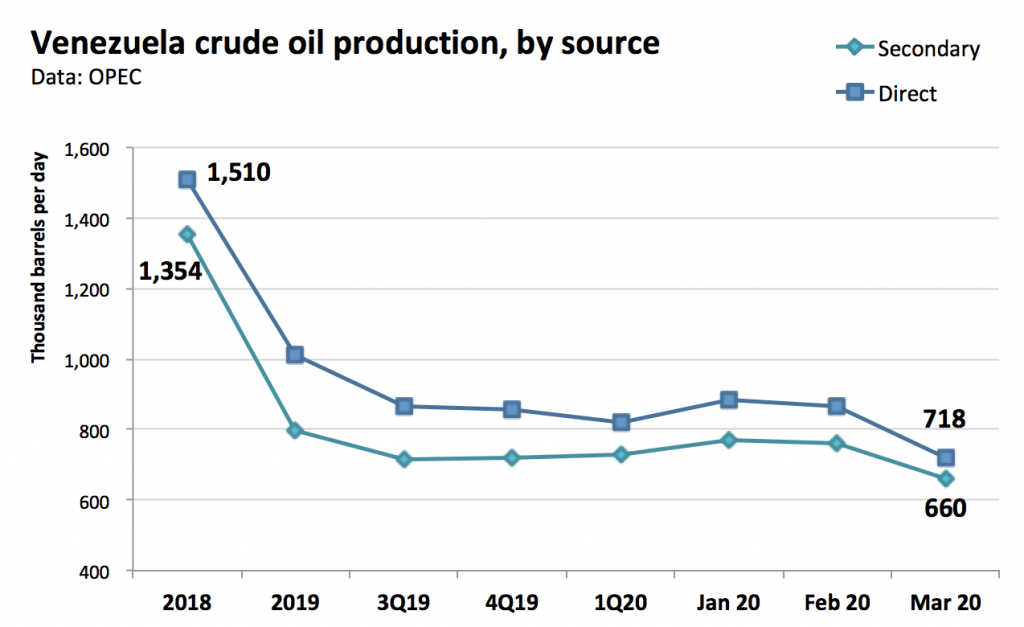

These measures will likely further decrease Venezuela’s oil production. According to OPEC data, the country produced 660 thousand barrels a day in March of this year, 100 thousand less than in February. Moreover, Fernando Ferreira, a geopolitical risk director at Rapidan Energy, estimates that daily production dropped to 500,000 barrels since mid-March.

The license in force will expire later this year, on December 1. CNN Business reported that the oil transnational “will likely request a license renewal” after the deadline, wanting to maintain a limited presence in Venezuela. If granted, it would allow the company to celebrate its 100 years of presence in the country and hold its position until the relationship between the two countries permits Chevron to resume its production.