Last week marked a historic milestone in the history of the United States: Kamala Harris was elected as the first woman vice president in the history of our country. Black and Latina women, once some of the most marginalized groups in the American electorate, were crucial to her election. During her first official appearance as vice president-elect, alongside president-elect Joe Biden, Harris wore a white suit by the Venezuelan-American designer Carolina Herrera, a nod to the women’s suffrage movement, long associate with the color white. “I stand on their shoulders,” Harris said of all the women who came before her, paving the way for this moment. In their honor, we look back at the suffragists, particularly the Latina women, whose fight at the beginning of the 20th century made our vote, and the election of a woman vice president, possible.

During the early 20th century, women suffragists all throughout the country lobbied, marched and fought for woman suffrage, both at the state level and federally. Latina women played key and sometimes overlooked roles in this fight, particularly in the Southwestern United States. They stood up not just for all women to gain the right to vote, but for Hispanic women to be included in the process.

In California, Maria Guadalupe Evangelina de Lopez became a leader in the California suffragist movement and an important asset in translating suffrage speeches and pamphlets from English to Spanish in order to reach wider audiences. She became both the youngest and the first Latina instructor to teach at UCLA. Like other suffragists, she was an active member of the Votes for Women Club, which sought to pass California Proposition 4, which would grant women the right to vote in the state. In 1911, the year the proposition was to be voted on, Lopez gave an unprecedented speech in Spanish during a large rally, and continued to work as a translator throughout the campaign.

(League of Women Voters)

On October of 1911, Proposition 4 was passed and California became the sixth state to give women the right to vote in the country, nine years before the passage of the 19th Amendment. Lopez went on to become the president of the College Equal Suffrage League. That same year, she published the bold assertion on the Los Angeles Herald that men and women deserved equal rights and that they should not be distinguished by gender under the foundations of democracy.

A similar movement was taking place in the neighboring state of New Mexico. During 1915, women suffragists demanded (unlike the rest of the American West, which, like California, focused on state efforts) that a national amendment be passed to give women the right to vote. In 1912, they had been unsuccessful in their fight to include woman suffrage in the New Mexico Constitution.

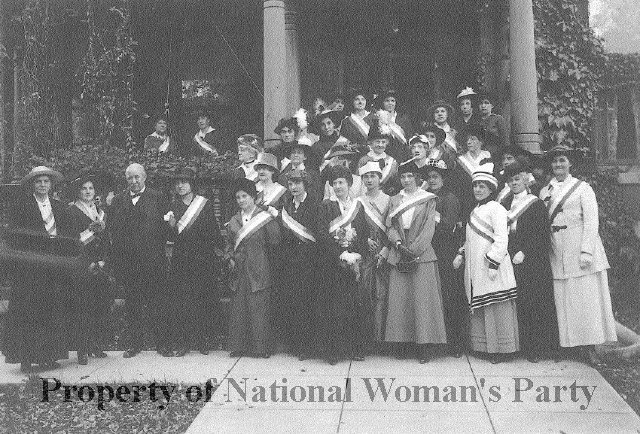

(National Woman’s Party)

Suffragists like Trinidad Cabeza de Baca, Dolores “Lola” Armijo, Adelina Otero-Warren, James Chavez, Aurora Lucero, Anita Romero and Arabella Romero took to the streets for the cause of woman suffrage, their advocacy for the vote growing out of their insistence that Spanish-Americans (as they called themselves) were equal citizens to their white counterparts. They insisted that the National Woman’s Party (NWP) work with and include Spanish-speaking women, helping with translations to include bilingual publications and speeches in the movement.

These Latina women shattered glass ceilings long before such term was coined. Armijo had become the first female member of state government when she was appointed as a state librarian in 1912. Otero-Warren was the first female superintended of Santa Fe schools. In 1915, New Mexican Senator Thomas Catron declined to support the federal amendment. Nonetheless, their fight continued.

In 1916, New Mexican women founded an official state branch of the NWP in New Mexico, which elected Otero-Warren as state vice-chair. Finally, in 1920, the 19th Amendment was passed, and the NWP played a critical role in getting the state legislature to ratify it in February of that year. In 1922, Otero-Warren was nominated as a Congressional candidate by the Republican Party. Though she beat the male incumbent during the primary race, she lost the main election narrowly. That same year, the Democratic nominee for secretary of State, Soledad Chávez de Chacón, became the first woman in the country to win election for that office.

(Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons)

As Kamala Harris pointed out, we stand on the shoulders of those who came before us. As we celebrate our first woman vice president, we commemorate these Latina women and the many others, of all ethnicities and races, who gave us the right to make our voices heard.