During the past couple of years, illegal mining in Venezuela has expanded under the Maduro regime. These practices are endangering the neighboring communities, which have been the victim of mutilations, disappearances, murders, and poor working conditions, as well as increased exposure to mosquitoes carrying malaria. Meanwhile, the authorities have turned a blind eye when it comes to protecting these people. Furthermore, they stopped reporting statistics on these crimes, making it difficult for organizations to understand the gravity of the matter. Still, despite the obstacles, international and local organizations concerned with human rights and environmental preservation have been able to gather critical information from their research and interviews.

On February 4, the Human Rights Watch (HRW) published an article precisely raising concerns about the human abuses in illegal gold mines in Venezuela. The text reports on dozens of testimonies from Venezuelan reporters, mining workers, and others living in proximities to the pits, as well as prior research on the topic.

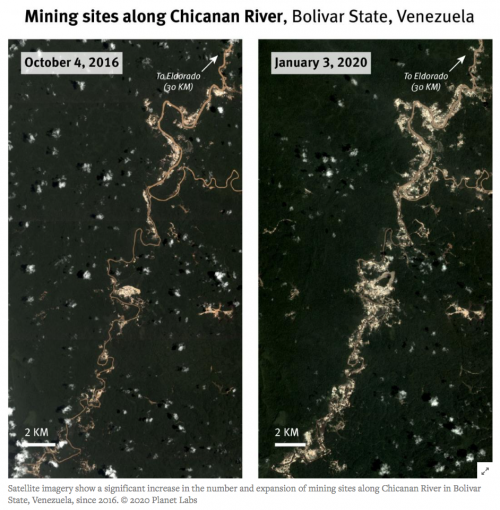

Here’s some background on Venezuela’s mining industry. In 2011, then-President Hugo Chavez announced the project Orinoco Mining Arc located in the Bolivar state. The purpose was to nationalize the exploitation and export of precious rocks and metals. Then, on February 24, 2016, President Nicolás Maduro created the National Strategic Zone of Development of Orinoco Mining Arc to develop an area corresponding to 12% of the country for mining purposes. The following satellite image shows the growth of mining practices in less than four years.

It is worth noting that Maduro signed the decree in violation of the Venezuelan constitution. First, he did not get approval from the opposition-led National Assembly. Second, according to the 2019 report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and accounts of members of local indigenous communities interviewed by HRW, the government did not consult with indigenous communities beforehand nor assess the environmental impact of the project.

Despite the Venezuelan regime’s decree nationalizing its mining industry and planning to extract gold, according to HRW’s assessment, most of the gold mined in Venezuela is illegal. A 2016 Reuters article quotes Maduro declaring the government had signed over $5.5 billion deals with foreign companies. Yet, as of a year ago, the International Crisis Group stated that there still was no major deal with foreign firms, and most mines are under non-state armed groups.

The HRW article goes on to report that the Venezuelan state company, Minerven, “received its gold from non-state affiliated mine operations,” which then is transported by the military to the Central Bank in Caracas. According to miners who have worked for Minerven, this is only a small portion of the gold production. Most of it is smuggled out of the country.

Multiple the testimonies gathered by HRW agree that mines in Bolivar are under the control of either Venezuelan syndicates or Colombian armed groups (both ELN and a dissident FARC group have a presence in the area). Five residents “said they had witnessed shootouts between Venezuelan security forces and syndicates, or between syndicates and members of Colombian armed groups, in what appear to be efforts to gain control of the mines and the revenue from them. In several cases, dozens of people, including women and children, died or were injured in these shootouts, the residents said.”

These non-state groups also “brutally enforce their rule.” Detailed descriptions obtained by HRW describe disappearances or public amputations on and shootings of people accused of stealing. More gruesome details can be found in the article.

Miners described working 12-hour shifts without protective gear. Among the workers, you can find children as young as ten years old. They are “required to pay a large portion of the gold they obtain—up to 80 percent—to the syndicate.” The miners and nearby residents are exposed to mercury, which is illegal but used to identify gold.

Perhaps the only indirect consequence of the mining activities in Venezuela is the growth in Malaria cases. However, it is still the responsibility of the government to address national public health. The large mining pits in the middle of the forest retain much of the rain, becoming breeding pools for malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

According to a report by the Pan American Health Organization, from 2010 to 2018, malaria cases in Venezuela increased by 797%. Most cases were identified in the states Amazonas, Bolívar, and Sucre. “Nearly every person interviewed who had worked in mines or mining towns had had malaria, many of them multiple times.”

Accounts obtained by HRW say Venezuelan authorities are aware of the illegal mining activities. Some, including two journalists and a local indigenous leader, said that government security agents had visited the mining sited to collect bribes. Two workers and the indigenous leader place a top official from the Maduro regime at the mines in different occasions.

Maduro and other Venezuelan authorities have announced intentions to fight against illegal mining and hold perpetrators accountable. However, they have not made any information public but “claim they have issued arrest warrants for 39 people allegedly involved in selling gold abroad, including Minerven’s vice president. According to the Attorney General’s Office, 32 arrest warrants that were issued have yet to be executed, nine people have been arrested, 12 charges filed, 426 bank accounts blocked, and 45 vehicles retained relating to gold smuggling as of August 2019.”

It is crucial to shine a light on this matter and hold these groups accountable for their human rights and environmental violations. Moreover, the Venezuelan government should report on the statistics of the crimes committed by non-state groups rather than turning a blind eye. According to local statistics, over 50 people have disappeared in the past seven years. However, the numbers must be more significant due to the inconsistencies in reporting statistics.