On August 3rd of 2019, Patrick Crusius drove 11 hours to the city of El Paso, Texas. There, he walked into a Walmart and began to shoot. “The Mexicans,” he confessed as his target when detained by police. Before the attack, Crusius wrote a declaration explaining the objective of the massacre he was about to commit: “a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas.” 22 people died, and 26 others were injured.

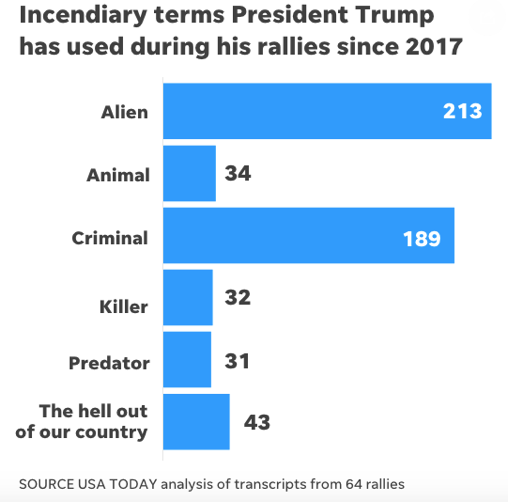

An analysis of “incendiary terms” used by President Donald Trump in 64 speeches touching on the subject of immigration between 2017 and August of 2019 shows a dangerous rhetorical pattern. In these speeches, he used the word “alien” 213 times, and “invasion” at least 19. The analysis showed that Trump was four times more likely to use the word “alien” to refer to immigrants than the word “immigrant” itself. In an Iowa speech last year, he told his supporters that our nation was “on track for 1 million illegal aliens trying to rush our borders. It is an invasion.” In conjunction with the terms “alien” and “invasion,” Trump used the terms “predator,” “killer,” “criminal,” and “animal” more than 500 times to refer to immigrants.

On social media, additionally, the Trump campaign has flooded platforms with warnings that the United States is under “invasion” by immigrants coming across the border. Facebook political advertising data revealed that the campaign funded the publication of over 2,000 political ads that urged users to, for example, “STOP THE INVASION.”

On May, before the El Paso massacre, President Trump gave a speech in Florida about the migratory crisis at the border. “Shoot them,” a member of the audience screamed, and Trump laughed. Three months later, Crusius did just that. He utilized the same rhetoric employed by President Trump to explain his objective of stopping the “invasion” of immigrants.

What is most troubling about this rhetorical trend in immigration discussions is that the term “alien” is currently the legal term most used by US immigration agencies to describe immigrants or foreigners in the United States. Just last week, the White House issued a presidential memorandum titled “Memorandum on Excluding Illegal Aliens From the Apportionment Base Following the 2020 Census” (more on this decision here).

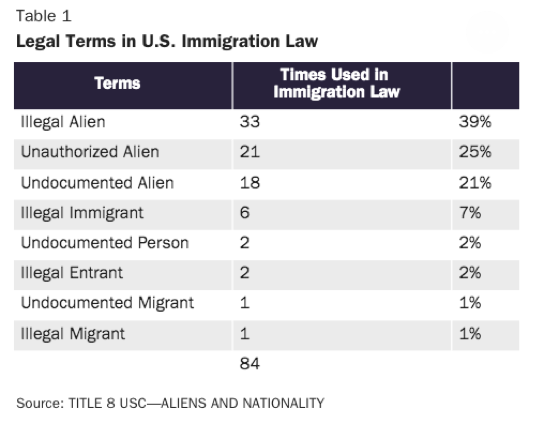

Today, the word “alien” is codified in the federal immigration laws of our country: the following graph shows the terminology most used in immigration laws, 85% include the word “alien” and 49% the word “illegal.”

The term “alien” comes from the Latin word alienus, which means “stranger” or “foreigner.” At the end of the 18th century, “aliens” were people born outside the domain of the King of England. In 1790, the term “alien” was included in the U.S. Naturalization Act, approved by President George Washington, the first document that established norms to grant American citizenship to “free, white aliens.” In 1798, President John Adams passed the Alien and Sedition Act, which authorized the President to expel “aliens” who were deemed dangerous to the peace and security of the United States.

Laws like these continued to appear for decades to come: Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which prohibited immigration of working classes from China. In 1924, the country instituted a nationality quota system, giving preference to immigration from western and northern Europe and assigning visas based on national and racial desirability. In 1965, ironically under the Statue of Liberty, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act, which for the first time restricted immigration from countries in the Western Hemisphere. A modified version of this document is now Title 8 of the United States Code, and contains the immigration laws that cover “Aliens and Nationality.” Since 1940, when Congress passed the Alien Registration Act, the Department of Homeland Security assigns to all non-citizens of the United States a series of numbers preceded by the letter “A” for “alien.”

Evidently, the term “alien” is a word with a racist and xenophobic past and dehumanizing and violent connotations, and it is time we adjust our terminology accordingly. It is not the first time that American legal terminology has fallen behind popular usage and appropriate standards. Derogatory terms such as “negro” and “oriental,” for example, remained in federal law until 2016.

The term “alien” and the proliferation of its use under the current administration have been conducive to resentment against immigrants and even massacres like that of El Paso by people who view immigrants and asylum seekers as invaders of the United States. It is not difficult to identify why the term has the effect of fostering fear and mistrust towards immigrants: according to the Oxford English Dictionary, an “alien” is “a foreigner, a stranger, or an outsider.” Or, alternatively, someone who is “opposite, disgusting.”

Since 2010, campaigns such as the Applied Research Center’s “Drop the I-Word campaign” have urged the media and the public to stop describing immigrants as “illegal.” Thanks to pressure from immigration advocates, in 2013 the Associated Press updated its rules and stopped sanctioning the use of phrases like “illegal alien,” explaining that the word “’illegal’ should describe only an action, not a person.”

Attempts have also been made to modify the legal terminology in our immigration system. In 2015, Texas Democrat Joaquin Castro introduced, without success, a bill to eliminate the use of the word “alien” in federal law and by US immigration agencies. Castro explained that “the United States is a nation of immigrants, however, our federal government continues to use terms that dehumanize and exclude those in our society who were born elsewhere” because “when someone says ‘aliens’ we think of Martians or aliens, not of humans.”

Some states have been successful in this effort. For example, in 2017 California passed a law that removed the word “alien” from the state’s labor code, recognizing that the word “alien is now commonly considered a derogatory term for a foreign-born person and has very negative connotations.” The New York City Commission on Human Rights in 2019 approved a new guideline that outlaws the use of the terms “illegal alien” or “illegals” with the “attempt to degrade, humiliate or harass a person,” with fines of up to $250,000.

We can look at the immigration terminology of other English-speaking countries to prove that the word “alien” can easily be replaced. In Canada, for example, the term “alien” is not used in federal statutes. Canada uses the term “foreign national” as its equivalent. The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act defines a “foreign national” as “a person who is not a Canadian citizen or permanent resident, and includes a stateless person.” The Australian Nationality Law defines people who are not Australian citizens as “permanent residents, temporary residents, or illegal residents (unlawful non-citizens).” The document only uses the word “alien” twice to refer to “enemy aliens,” or people from countries at war with Australia.

“Foreign national,” “immigrant,” “asylum seeker,” “migrant” “foreigner,” “non-citizen,” “undocumented,” “non-native.” All these terms and more can be used to describe an immigrant or foreigner, documented or not. When there exist so many alternatives, the continued use of the word “alien” is indefensible.

Immigrants are not “aliens.” Behind every one there is a story about why they decided to make the difficult decision to leave their country. Many immigrants have no other choice, and each of us sought the same thing: a better future. We do not leave our country to “invade” another. We are not “animals,” “criminals,” “killers,” or “predators.” And we are not “aliens,” we were simply born outside of the United States.

We must demand from our leaders that they do not instigate discrimination against immigrants or violent acts such as the El Paso massacre. We must demand that they speak about human beings who make the decision (or are forced) to leave their home countries in a dignified and respectful way and that they be aware of the weight of their words. For this to happen, the immigration laws of this country cannot continue to sanction terminology that encourages otherwise. Knowing what we know about the history of the term, about how it makes the people it describes feel, about the feelings of distrust and violence it encourages, and about all the alternatives that exist, there is no reason for the United States, a country of immigrants from its beginnings, to continue to use the derogatory, offensive and dehumanizing term of “alien.”

Photo: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration