We continue our series analyzing the hemisphere by shining a light on the Republic of Suriname. Together with the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, despite being located in South America, it has a closer bond with some Caribbean islands or European nations and barely some with its neighboring countries Brazil and Venezuela. They are located in the northeast corner of the continent that faces the Atlantic Ocean. Still, their realities mostly happen alien to that of its neighbors.

There are historical and linguistic reasons to explain this phenomenon of proximity and distance. In the case of Suriname, it is the only country in the continent whose official language is Dutch (the official language of the Netherlands). In fact, for a long time, it was called the “Dutch Guiana.” Since the beginning of the 16th century, both British and Dutch had a presence in the region. In 1677, the Dutch empire famously handed over the territory, then known as New Amsterdam (what is New York City today), to the British in exchange for the full control of the region occupied by Suriname. Centuries later, in 1975, Suriname achieved its formal independence from the Netherlands. Once the new statute was established, the new republic received help from the Netherlands Development Fund until 2012.

Additionally, concerning this initial relationship, since Suriname’s independence—just 45 years ago—approximately one-third of the population emigrated. Over 200 thousand people left Suriname, most of them mainly to the Netherlands, the very nation from which they had liberated. Consequently, Suriname lost about 50% of its workforce, which included entire layers of technicians and professionals. Among those who migrated are children and young people who would become famous soccer players. Now they are the stars of European teams and even members of the national Netherlands team.

In its recent history, this loss of talent has created difficulties for the economy and management of the country. Its territory, of almost 164 thousand square kilometers, places it as the smallest in South America, even below Uruguay, which has about 176 thousand kilometers. Today, an estimated 578 thousand people make up its population. Of that total, about 250 thousand live in the capital, Paramaribo, and approximately 400 thousand inhabit the metropolitan area.

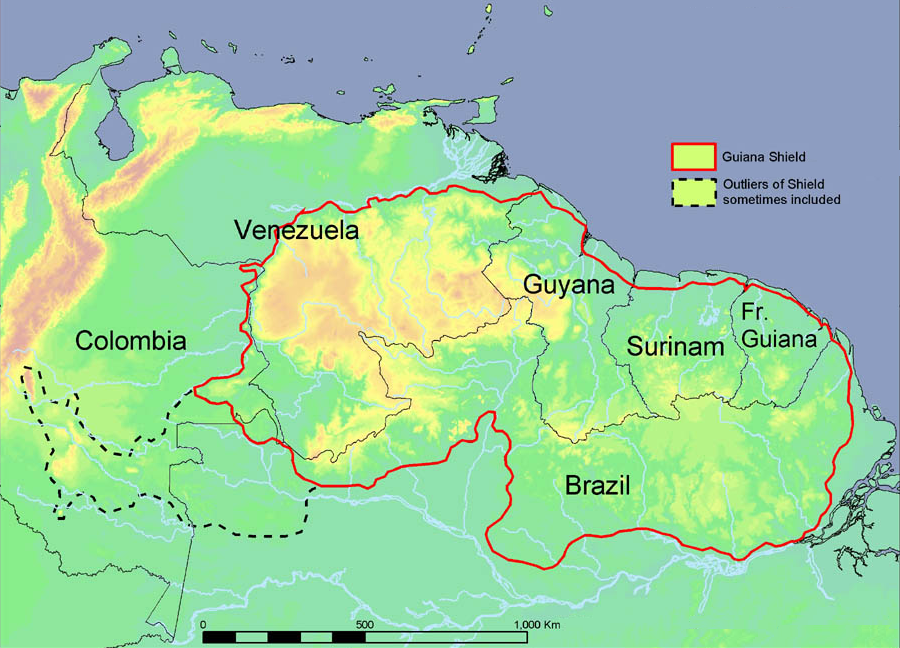

Almost all of Suriname—what can be called its interior territory—is located on the so-called Guiana Shield, which is one of the oldest geological formations on Earth. It is an immense territory of wonders shared by Colombia, Brazil, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana (French overseas territory located east of Suriname). High-density forests predominate in the region, where they get the wood they export.

Suriname’s main economic foundation is the export of products of mineral origin. Between 2015 and 2016, a powerful financial crisis impacted the lives of the Surinamese. In addition to the closing process of Suralco, the primary aluminum plant, owned by Alcoa, in 2015, global prices of raw materials such as oil and gold fell. The effects were considerable: the currency was devalued around 55%; inflation exceeded the annual rate of 60% (it was the third-highest in the world, after Venezuela and South Sudan); hospitals ran out of supplies; there was a shortage of basic goods spread throughout the country. The situation produced such levels of anxiety that street conversations repeated that Suriname was following the footsteps of Venezuela.

In its 2019 report, ECLAC described a slight improvement from 2017 with a 1.7% growth that year. In 2018, the figure achieved a minimal increase: 1.9%. According to the forecasts of the same agency, 2019 likely closed at a rate of 2.1%. The sources of growth are none other than exports of gold, oil, and some agricultural produce such as bananas. According to World Bank forecasts for the years 2020 and 2021, the country will maintain a modest growth rate of 2.1% on average in both years. During the mentioned period, inflation has been decreasing gradually.

In the Macro Data portal, of the newspaper Expansión de España, which keeps an updated track of the main economic figures of all countries, Suriname appears as the 16th economy. In 2018, the GDP per capita was 5,338 euros (around 5,600 dollars). The World Bank, meanwhile, estimates a lower figure for the same 2018: 5,210 dollars. It should be added here that, in a 2016 report, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) estimated that remittances represent around 3% of GDP.

Depending on the method used to determine the level of poverty in Suriname, the number varies considerably between 50 and 70% of the population. In 2015, the World Bank reported an unemployment rate of 9%, which doubled (18%) for the population between 15 and 24 years. The IDB report mentioned in the previous paragraph notes:

“Although almost 5% of GDP is invested in education, about 12,000 school-age children in Suriname do not attend school. Although there have been advances in the last decade, many young people still do not have access to secondary education. In 2013, only 56% of students who completed primary education joined secondary school. Repetition rates are high: 16% of students at the primary level and 14% at the secondary level repeated grade in 2011. Suriname does not participate in international school performance tests, so there are no results evaluations of learning. During the last 40 years there have been no major reforms of the system. General access and efficiency indicators conceal deep regional and gender disparities. The disaggregated data show that there are specific groups of the population that are underserved by the system. The gap between districts is important, and the interior is far behind the urban areas in most of the indicators.”

The country’s statistics system difficulties, also noted by the IDB, make it hard to obtain trends and data that have a sufficient understanding of the status of social indicators. The institute of official statistics’ website is not easy to use for those who visit it.

While the public sector is large, the private sector is small and concentrated in two activities. The first is dedicated to mining and exporting minerals and by-products. The other one focuses on commerce and the distribution and sale of products, most of them for basic needs, which is necessary for the families to use. This accounts for one of the most critical issues pending on the country’s public agenda: a barely diversified economy, extremely dependent on raw materials, that is, tied to goods that are permanently subject to price variations. A few words from 2016, by Gillmore Hoefdraad, Minister of Finance, are revealing the criteria that prevail in Suriname’s economic policy. He said then: that the crisis was temporary because “gold and oil prices would soon recover.” At that time, the government hoped to increase its budget, once a mining company in the United States began operations in its territory.

Analysts who know Surinamese history and culture have insisted on pointing out ethnic-cultural diversity as a structural difficulty in consolidating a necessary project for the country. The mosaic has been a factor that has not facilitated the articulation of a civil society capable of pressuring the government and institutions. The ethnic and human tapestry is very varied: there are people from Africa, China, India, Indonesian islands, Europe, and Aborigines. Also, those that are the result of mixtures of these primary groups, such as Creoles and Maroons, must be added.

In the middle of this structural barrier—typical of the mining countries with the mentality of the rulers and the absence of public policies that are the platform to diversify the economy and provide society with an educational system with a vocation for the future—Suriname is going through a situation that could foreshadow a significant political crisis.

On November 30, 2019, while on a trip to China, a military court sentenced Desiré Delano Bouterse, President of Suriname, to twenty years in prison. The sentence derives from the trial for the murder of 15 citizens of the opposition, in December 1982. Bouterse led a coup d’etat known as the “Sergeant Revolution,” which made him the country’s strongman until 1991.

The fact that the trial in question began in 2007 suggests the power of the ruler in his small country and the scope of the court’s decision. The text does not order his immediate detention. Countries such as France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and the United States demanded the immediate arrest of the accused. Bouterse returned to Suriname and said the accusation is a political retaliation. While his lawyers have announced that they will appeal, the convicted has declared that he has his agenda focused on the elections next May.

The former is not the only legal complication of Bouterse. In 1999, he was sentenced to 11 years in prison in the Netherlands for drug trafficking. He could not be extradited because that procedure is not contemplated in the laws of the country. More recently, Bouterse reappeared in a drug trafficking investigation, but this time in a video where Jesus Santrich and two other people, in addition to talking about money and drugs, repeatedly mention Bouterse and the help he would provide them. The president’s son, Dino Bouterse, has been twice imprisoned in the United States, prosecuted for cocaine trafficking, stolen vehicles, and weapons, which link him to the Hezbollah terrorist group.

After repeated and successful maneuvers to delay, hinder, and deactivate the trial against him, after thirteen years of fluctuations, the sentence occurred. But this sentence, as Bouterse has stated, will not prevent him from participating in the presidential elections that will take place in May. There are opposition leaders who have expressed concern about the transparency and control that the candidate president could exercise over the elections, for his benefit. The perception of fraudulent elections could generate acts of violence.

It may not be an exaggeration to affirm that both the electoral process and its results will be decisive in the future of the Republic of Suriname. Surinamese society could start a new stage in its history, surpassing the rentier vision that has prevailed so far by designing an inclusive country project to insert Suriname into the significant challenges of the moment, among others, those derived from the digital revolution.

Nos leemos por Twitter @lecumberry