The separation of powers was a term coined by Baron de Montesquieu in 1748 in his work “The Spirit of Laws”.The concept was meant to describe how the government was meant to be divided into three separate branches: Executive, Legislative, and Judicial.

These branches work as independent and distinct bodies in order to limit any one of these from garnering more power. Furthermore, they not only act as “checks and balances” for each other, but also distribute the political power in order to guarantee political freedom and avoid abuses of this power through mass surveillance, as well as reciprocal control from these divided bodies.

However, as history has shown us in Latin America, this is very normative and far from the reality of these governments. Latin America has been characterized by not having transparency between powers. Coupled with the Latinamerican systems where it is easy to amend the constitution, the region generates more corrupt governments.

This reality, in turn, begs the question as to how the legal system of these countries can act and proceed in an orderly fashion when the judiciary system is heavily influenced by the executive power’s political agenda or even makes decisions based on their own political views.

With this being the case, how can families who have been victims of crimes against humanity have any hope of obtaining justice? Or by what means can countries breed environments of legal continuity when at the end of the day political agendas determine the fate of those trialed?

The lack of clear state intention to find the victimizers comes at the face of State Supreme courts almost intentional resistance of applying international law, and quick dismissal of the existence of crimes against humanity within the time period of these governments, which committed such crimes, because of their views on the matter.

Francesca Lessa, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford, wrote a policy brief on the investigation of crimes against humanity in South America. In it she explains how the judiciary reacts against the forwarding of the military dictatorship cases in Uruguay form 1973-1985, which touch on these crimes. “The Supreme Court has maintained that crimes committed during the dictatorship were not crimes against humanity, creating a situation of judicial insecurity that affects the victims and favors the impunity of the victimizers.” This points to one of the political realities that I previously mentioned, where you have a Supreme Court negligently ignoring the facts, based upon their interests on the political situation.

This same Supreme Court penalized Mariana Mota, one of the judges on duty during some of the cases, because of her open participation on protests against the Supreme Court’s behavior, further noting the open rejection of political opposers that threaten their power.

Now, this occurrence is not exclusive to a certain political ideology. In fact, governments who are believed to protect the values of liberalism are also culprits of this kind of behavior. Take for example the recent case Mauricio Macris’ Argentina.

Lorena Balardini, a researcher at the University of Buenos Aires, alongside the Procuratorate of crimes against humanity in Argentina, has compiled extensive information that shines light to the current situation in Argentina. The evidence grants this general context as what’s happening.

Considering 10% of prosecuted defendants are dismissed for health reasons and 565 die before even reaching trial, there is greater evidence to support the argument of a systematic biological impunity system. According to the Procuratorate of crimes against humanity in Argentina.

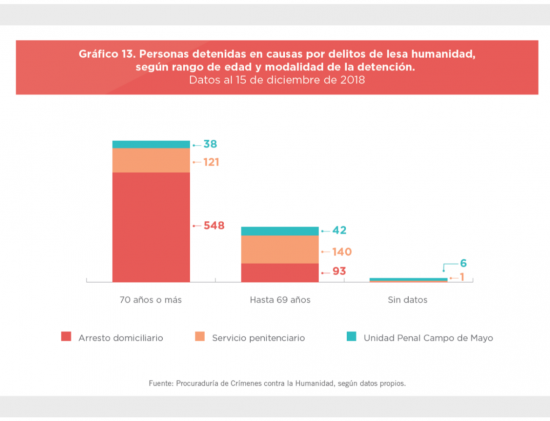

Further data indicates that the detained-to-free ratio of the people investigated for these crimes has grown exponentially. Additionally, you have a situation where the people investigated are mostly over the age of 70. As a result, punitive action is often disregarded over house arrest, letting these people live their lives without serious repercussions.

During 1974-1983, Argentina was under a military dictatorship. During this period, this right-wing dictatorship was involved in Operation Condor, a US-backed campaign officially implemented on November 1975. The goal of the Operation was to repress political opponents and create state terror. They did this throughintelligence operations and the assassination of opponents.

Now, because of this being a right-wing operation, led by the US, there is some correlation to the evidence that Macri’s government and the special interests, who helped him get there, share a common objective not furthering these cases.

Nevertheless, it is clear that with these realities in mind, the environment to create a space where the rule of law precedes the political stances that those in power have, has to be fostered and incentivized from within. Additionally, measures have to be taken in order to cultivate transparent and distinct branches of government.

Politics will always play a role in the Judicial system of Latin American countries. However, what matters is to what extent we can let the system be contaminated by those who want to influence it. If politics play this role, then it is paramount for people to demand the values of the law to be respected, including the international community taking hard stances against this behaviour.

If this is achieved, all aspects of life will flourish. Since we have to start somewhere, why not with our human rights?